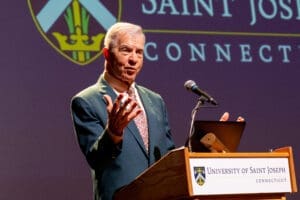

WEST HARTFORD – (Oct. 30, 2024)-Dr. James Perry, an internationally recognized leader in public administration and the study of public management, was the speaker at the second annual University of Saint Joseph (USJ) Deans’ Lecture, held Tuesday, Oct. 22 in Hoffman Auditorium. His presentation, “Walking the Moral Tightrope of Public Service,” examined the commitment public servants make to public duty without regard to partisan politics.

Perry, a pioneer of public service motivation research is distinguished professor emeritus at the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University, where he is also an affiliate professor of philanthropic studies.

The lecture series was created by USJ’s three deans: Dr. Karl Besel, dean of the School of Interdisciplinary Health, and Science; Dr. Ahmed Abdelmageed, dean of the School of Pharmacy and Physician Assistant Studies; and Dr. Raouf Boules, dean of the School of Arts, Sciences, Business, and Education. The first Lecture featured USJ alumna, U.S. Treasurer Lynn Mutawi Mutasash (Many Hearts) Roberge Malerba’83, H’10, DAA ’17.

“This lecture series is an ongoing endeavor in which the three USJ deans collaborate to bring distinguished speakers to our campus and engage our community and that of Greater Hartford in an evening of ideas and inspiration,” said Dean Besel.

In her introduction, USJ student Trinity Thompson, president of the MSW Student Association, called Perry “a modern-day trailblazer and significant contributor to the field of social work and human services. Because of Dr. Perry’s dedication, students like me are motivated to be the change we want to see in the world.”

Perry began his presentation with two questions: “What is public service motivation… and what is it that drives the behavior of people who join public service?”

Perry began his presentation with two questions: “What is public service motivation… and what is it that drives the behavior of people who join public service?”

He shared a story about a conversation that he said took place between a social worker and an MBA, in which the MBA, only thinking about money, asks the social worker, “What do you make?”

“The social worker responds, ‘You want to know what I make? I have made safe places for abused children. I did my best to make them feel that they don’t deserve the treatment they got so that they could go out and do better in their lives. I now make arrangements for the terminally ill to stay at home in their last days with exceptional end-of-life care. We make visits to neighborhoods that most people won’t go to on a map, because we know people there are in need. We make time to listen to the elderly, the mentally ill, the lonely. We make appointments with officials and testify before the legislature to give everyone in the community a fair shake.

“‘So, when people want to judge me by what I make, I hold my head up high and say, I make a difference. What do you make?’”

“And that, to me,” explained Dr. Perry, “captures the spirit of public service motivation and this give-and-take between someone who’s in their career for the money—for the financial and tangible rewards— and someone who’s in their career for other reasons, reasons that I associate with this idea of public service motivation.”

Perry spoke about several heroes that he believes made a difference in the world of public service motivation, starting with John F. Kennedy who came to Perry’s hometown in Wisconsin when he was running for President.

“John Kennedy inspired me. And one of the things I remember well from his Inaugural Address is this statement—’Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country’” He also listed Paul Volcker, the economist who served as chair of the Federal Reserve Board under Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan and noted Volker’s premise that 2% inflation is the measure of price stability.

“The 2% came from Paul Volcker because he believed in the Federal Reserve as an important American institution that can make lives better for American people across the country…Paul Volcker stepped up; he upped the interest rates to double digits, and he broke the back of inflation.”

Perry also named Paul O’Neill—namesake of the School of Public and Environmental Affairs of which Perry is emeritus— as a hero.

“He became Secretary of the Treasury under President George W. Bush, and he lost his job. Why did he lose his job? Because he had the courage to tell President Bush that cutting taxes was not the way to make life better for most Americans. Again, he used his voice out of respect for his commitment to the public interest.”

A more recent hero, Perry notes, is Anthony Fauci, former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and his efforts to help eradicate HIV/AIDS and to facilitate the development of the COVID-19 vaccine.

“He exercises compassion. I list him as an exemplar of self-sacrifice. Why? Because he could have made billions of dollars by going into private practice. Instead, he said, ‘no, I want to go to work for the National Institutes of Health.’”

Dr. Perry listed four motivators that drive many into public service: to sustain the system, duty or obligation, compassion, and self-sacrifice.

“Why would somebody enter public service? One reason is to sustain that system of our democratic enterprise. It is to sustain our way of life, our representative democracy, so citizens can have a role in their government,” he said. “We have Congressional staffers and others who join in those jobs because they say this is going to make the system work, and I want to sustain the system. So that is one facet of public service motivation, from my perspective.”

Others come to public service because, he said, they “want to pursue the public interest, whether that be in the environment area, or in the social betterment area or in the education area. They see it as either a duty or an obligation.”

“A third dimension is compassion, which I define here as love for others in the imperative that they must be protected. Compassion is just not sort of a bleeding heart, but it is a real commitment to one’s fellow man and woman and fellow members of society. It is a commitment to making their lives better….”

“Finally, one that I again connect to John Kennedy— self-sacrifice— which I think tends to be common to most people who are pursuing public service…they say, ‘I’m not going to make money in government, but I will go into government because I will make a difference for other people.’”

Dr. Perry finished with a moral dilemma that public servants experience, particularly when dealing with political superiors.

“Most civil servants in the Federal government came to their roles because of their expertise and willingness to work with people from both parties,” Dr. Perry said, referring even to public servants appointed through meritocracy—getting their job because they are competent, and they do their job well. “But clearly, one of their moral dilemmas—one of the tightropes they have to walk—is subordinating their interests to those of their political superiors. Because our system says that the bureaucrat—the civil servant— is the agent, and they need to be looking up the chain of command to serve the interests of the political superiors.”

Where this can become a moral tightrope is when dealing with employment, discipline and dismissal, Dr. Perry said, referencing Schedule F, the job classification order signed by former President Donald Trump in October of 2020, which would have made federal employees in “confidential policy-making or policy-advocating” positions at-will employees and easier to fire. President Joseph Biden revoked Schedule F in January 2021 but this issue has come up again during the current election season, Dr. Perry said.

“At-will employment means that you serve at the pleasure of your superior. If your superior wants to fire you, you are out,” Dr. Perry explained. “But we have this other principle called just cause discipline and dismissal, which says that you could only be fired for cause, and that is embedded in the rules of our civil service systems and our government governance structure.

“The meritocratic appointment, meritocratic advancement and just cause discipline and dismissal are key attributes of American institutions, and I would argue they advance public service motivation, because competence is important to people with public service motivation.”