The interstate highways that were jackhammered through Hartford six decades ago may have increased vehicular mobility, but they did so at great cost to the fabric of the city. Now, a new plan — a mix of previous efforts, along with new ideas — aims to remedy that.

Decades ago, the construction of I-91 cut Hartford off from the Connecticut River. I-84 isolated the North End from downtown and consumed a large swath of land and many historic buildings, including the majestic Hartford Public High School campus. The interchange of the two highways laid waste to part of the central business district.

East Hartford wasn’t spared; its massive “mixmaster” interchange occupies an area the size of downtown Hartford.

The placement of the highways has been criticized almost since they were built. In the past decade, two strategies emerged to remediate the damage. One, developed by state transportation officials, proposed taking I-84 through the North Meadows and over a new bridge. The other, put forward by U.S. Rep. John Larson, would put both highways in an elaborate series of tunnels.

Neither of those concepts is moving ahead. The state abruptly pulled the plug on its process in 2019 to do a broader regional mobility study. Larson’s idea, which garnered some praise but considerable criticism as unworkable and dauntingly complicated, never gained traction.

Now a third idea, a hybrid that uses parts of the first two plans, has emerged and is being presented to civic and business officials, neighborhood groups, and others.

Is the third time the charm?

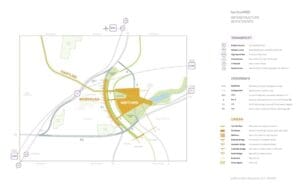

The new plan is part of a regional planning effort called Hartford 400, initiated by the iQuilt project in Hartford. It envisions a roughly triangular ring road around the downtown, with some tunneling but much less than Larson proposed, and new connections to East Hartford.

The preliminary cost estimate is $17 billion, over a period of 15 years.

For that investment:

The I-84/I-91 and “mixmaster” interchanges would be removed, freeing more than 150 acres of prime urban land for development in both towns.

I-91 would be capped through downtown Hartford. The cap above the highway would carry a new avenue bordered by new development on one side and new parkland on the other — effectively a 1.5-mile extension of Riverside Park. Thirteen downtown streets would connect to the new “River Road.” Through-traffic on I-91 would take the existing highway; local traffic would use River Road to access downtown.

The decaying 1940s-era river dikes would be repaired. This is considered essential, lest Hartford risk a Katrina-like disaster.

The portion of I-84 from Union Station to the Bulkeley Bridge — now an elevated curve dropping into a 200-foot-wide trench — would no longer be needed once the interchange is moved. Morgan Street would be restored as an urban avenue connecting Main Street to the riverfront. The North End would no longer be walled off but connected to the rest of the city.

A seven-mile linear park, an increasingly popular amenity and economic development draw in cities across the country would be built from Bloomfield along the little-used Griffin rail line to downtown and then to East Hartford.

Three new bridges would be built across the Connecticut River, dispersing traffic bottlenecks.

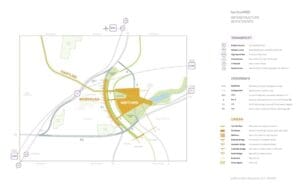

A diagram of the proposed realignment of I-84 and other parts of the Hartford400 highway plan.

The goal would be growth. Planners think with better-organized transportation and housing, the Connecticut Valley could add half again to its population (of about 1 million) without increasing sprawl, adding pollution or damaging the region’s New England character.

The plan is being well received, notably by Larson, who praised it as “brilliant” in a recent interview, saying it meets all of his infrastructure goals. He said he plans to put the Hartford 400 plan forward as part of the Biden administration’s proposed $2 trillion infrastructure program that is expected later this year. With the Biden plan coming and New England Democrats heading key Congressional committees, Larson sees “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

“We’ve got to be ready,” he said.

Gov. Ned Lamont and transportation commissioner Joseph Giuletti presumably would have to sign off as well, and neither has been heard from yet. Larson said he would be shocked if they didn’t support the proposal.

Broader Vision

The progression to Hartford 400 began about two decades ago with efforts to replace the 2.5-mile series of viaducts that carry I-84 through much of Hartford. About 80 percent of the 1960s-era roadway was built on bridge stanchions that had a projected 50-year lifespan.

The state Department of Transportation considered simply repairing the viaducts as they stood. But a citizen’s group, the Hub of Hartford, formed and said, in so many words, if you’re going to repair the highway, why not undo some of the damage it did to the city?

The DOT got behind the idea. The viaducts were repaired to extend their use, and in 2012, the department initiated a public planning process to determine the future of the highway.

The planners determined that bringing the highway down to, or slightly below, grade level was the best way to replace the viaduct system. It would allow city streets to cross the roadway, reconnecting the North End and Asylum Hill to the rest of the city.

But that didn’t solve the congestion problem. I-84 was built to carry 55,000 vehicles a day but by that time was carrying 175,000. Add the 100,000 on I-91, and the interchange of the two interstates was the worst bottleneck in the state and the second-worst in New England, according to the American Transportation Research Institute.

So, in 2016, then-DOT Commissioner James Redeker initiated a study of the I-84/I-91 interchange, looking for a way to reduce the congestion.

Then, in the winter of 2016-17, seemingly out of the blue, came Larson’s tunnel plan. The Congressman had for several years been trying to get federal funding to repair the river dikes, which the Army Corps of Engineers determined were in an “unacceptable” state of repair after a 2013 inspection.

Meeting with engineers about the dikes in the spring of 2016, Larson wondered if the traffic congestion problem couldn’t be solved with tunnels, with the rock from boring the tunnel going to shore up the dikes — two birds with tons of stone. He said more meetings followed, culminating in the tunnel proposal.

The concept called for an east-west tunnel running four miles from Flatbush Avenue in Hartford under the southern tier of the city and the river to the Roberts Street area in East Hartford. A north-south tunnel would run two miles from the North to the South Meadows. They would meet at a large cloverleaf intersection under Colt Park, which would add four to six miles of tunnels.

That would be at least twice the five miles of tunnels created in Boston’s Big Dig.

Larson asked DOT highway engineers to study his proposal. They did. They didn’t think it would work. The issues were cost, the complexity of an underground interchange and local traffic.

The idea — it was never crystallized to a formal plan — was that the tunnels would carry through-traffic while existing roads and bridges would become boulevards for local traffic.

The problem there was that most of the peak highway traffic — more than two-thirds at rush hour — is local, going to or from Hartford and East Hartford. So tens of thousands of cars would have to use the boulevards, likely increasing, rather than lessening, congestion.

The solution the DOT planners preferred was a “northern alignment,” which would bring I-84 on a new connector, capped in residential areas, through the Clay Arsenal neighborhood to the city’s North Meadows, to which the I-84/I-91 interchange would be relocated. I-84 would then go over a new bridge and reconnect to the existing highway in East Hartford.

Larson didn’t think this plan went far enough to recapture the river and continued to promote the tunnel concept. The DOT, which likes to stay on the powerful Congressman’s good side, pulled back the I-84 study in 2019 and replaced it with a three-year regional mobility study, saying the region’s infrastructure needed a “holistic approach.” So, the momentum stopped.

In 2007-08, the folks at the Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts initiated an urban design process to better connect downtown Hartford’s arts and cultural institutions and make the area more inviting for pedestrians and bicyclists.

They hired Doug Suisman, a Hartford native and scion of a prominent local family. Though Suisman was — and is — an internationally-known urban planner in Los Angeles, he had always kept in close touch with his hometown. He proceeded to design the iQuilt, a loose-footed network of public spaces, some new and some restored, running from the river to Bushnell Park and the Capitol. A nonprofit, the iQuilt Partnership, was created to execute the plan.

The “green walk” has made downtown — almost unconsciously — a more pleasant place to walk. By 2018, this central iQuilt project, with features such as Travelers Tower Square and the Bushnell Park promenade, was almost complete. The board and staff decided to keep the iQuilt effort going.

“A region should have an ongoing organization that’s a steward of the public realm,” Suisman said in a recent interview. The question was how to go forward.

Suisman recalled that Hartford was nearing its 400th anniversary, in 2035. Using that as a timeframe, the group, backed with a grant from the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving, created a visioning project for the Connecticut River Valley: what did the region want to be in 2035, and how might it get there?

The first step was to review almost 100 plans that had been done in the region over the years, from the Bradley Airport expansion, Riverfront Recapture, the Hartford Line, and the I-84 Project, all the way back to the construction of the Bulkeley Bridge in 1908 — “everything we could find,” Suisman said.

They were “looking for commonalities,” Suisman said, areas of agreement. Working in tandem with the Hartford Planning & Zoning Commission, which was preparing its plan of conservation and development also focused on 2035, they found “a lot of consensus” in the region on five broad goals: equity, economic growth, arts and culture, environmental sustainability and mobility.

On the latter, the highways were still a sticking point.

After studying the plans, Suisman concluded that the DOT and Larson had much the same goals but different approaches. It was about then that the DOT determined that the I-84/I-91 interchange had to be moved. In Suisman’s mind that changed everything — “It was a big deal.”

Instead of repairing a road, it opened the door to reimagining the whole system. “We asked, ‘What happens if you move the interchange? How can we figure this out as an economic development project?’”

The view of downtown Hartford looking north along a proposed new greenway.

Synthesis

Suisman saw strengths in both the DOT and Larson plans, so, over 18 months, he created a hybrid, a synthesis of the two. One point of the triangular plan, as with the two earlier plans, is the Flatbush Avenue access to I-84 in the western part of the city. Suisman’s plan uses a tunnel from that point to take I-84 to the Charter Oak Bridge and then over it, to reconnect with the existing highway in East Hartford.

The plan also uses the “northern alignment” road, which Suisman dubs I-891, from Flatbush along part of the I-84 corridor then through the North Meadows and over a new bridge to East Hartford. The third leg of the scalene triangle is the capped I-91.

Suisman and the consulting engineer Foster Nichols solve the daily downtown bottleneck by dispersing the traffic. Instead of a huge downtown interchange, there are two smaller interchanges, north and south of downtown. The northern I-891 route has five ramps to downtown. The river road atop I-91 connects to 13 downtown streets. In addition to the new bridge for I-891, Suisman envisions two more traffic bridges south of downtown, connecting the Coltsville and Brainard field areas to East Hartford.

Does the region need three new bridges?

The bottleneck coming from the east is caused by limited options, he said. For example, people coming west from Pratt & Whitney and Goodwin College have to use the highway. More bridges disperse traffic and better connect the South Meadows industrial area to Pratt and other East Hartford businesses.

“Look at Pittsburgh,” said Suisman, who has worked there. Sometimes called the City of Bridges, Pittsburgh claims 446 bridges, so many that bridges are part of the skyline.

If all goes according to plan, the Coltsville bridge will connect to a new neighborhood in East Hartford. The construction of the river dikes freed floodplain land in East Hartford for development, Suisman said, but instead, much of it was used for the massive mixmaster interchange. Removing it — just leaving a capped connector from the new northern bridge to Route 2 — opens a remarkable 130 acres of prime riverfront land for development. Suisman imagines an area called MidTown, a river-oriented mid-rise neighborhood surrounding a park.

The plan isn’t just about cars. It encourages active transportation — biking and walking — and accommodates the city’s new transit options. The multi-modal home run would be a connection to North Atlantic Rail, the proposed New York to Boston high-speed rail line, which planners hope to bring through Hartford.

Watch This Space

Suisman’s renderings of development on both sides of the river somewhat suggest Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive, with its waterfront parks, roadway, and mid-rise buildings. Lake Shore is the product of a well-known 1909 Chicago city plan by architect and planner Daniel Burnham, who famously said, “Make no little plans.”

Hartford 400 is no little plan. It might take 15 years to build and define the region for 100 years. Of course, the original interstate highway plan was also big.

“We have to get it right this time,” Larson said.

Much depends on the passage of Biden’s infrastructure bill. Larson stressed that funding would be separate from the normal federal funding for state transportation projects. He said the project could be built in stages, if need be.

But the initial response is positive.

“We showed it to 58 people last week and have not received a single negative comment,” said Jackie Mandyck, executive director of the iQuilt Partnership.

One audience member was veteran planner and consultant Toni Gold, who’s been involved with the Hub of Hartford, Riverfront Recapture, and any number of other Hartford initiatives. She is not an easy sell. But after a two-hour presentation, she said of Hartford 400: “I’m now persuaded that it is a great plan.” She noted, in particular, the idea of breaking the big I-84/I-91 interchange into two smaller ones north and south of downtown: “Very clever.”